Latest

Story

02 July 2025

UN's Panova says Egypt deeply committed to placing food systems, food security, and nutrition at heart of national development priorities

Learn more

Story

01 July 2025

Eighty years on, UN Charter marked by reflection, resolve – and a run

Learn more

Speech

01 July 2025

Launch of the National Operational Plan for Food and Nutrition Systems 2025–2030, and the Accelerated Anemia Action Plan

Learn more

Latest

The Sustainable Development Goals in Egypt

The Sustainable Development Goals are a global call to action to end poverty, protect the earth’s environment and climate, and ensure that people everywhere can enjoy peace and prosperity. These are the goals the UN is working on in Egypt:

Video

06 February 2025

Sustainable Development Goals in the Spotlight as UN Egypt makes debut participation at the Cairo International Book Fair

For the first time, the UN Egypt family participated in the Cairo International Book Fair, one of the most significant and influential book fairs in the Middle East.Throughout the event, the UN in Egypt's booth welcomed visitors of all age groups, offering them a chance to explore a selection of key UN and international publications and reports available at the UN Information Center in Cairo’s library—one of the oldest and most prominent libraries of its kind in the region.The UN Egypt booth also provided visitors with a diverse range of printed publications, digital materials, and videos aimed at raising awareness and sharing success stories, all highlighting the UN’s impactful contributions and its partnership with the Egyptian government to advance the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).These resources reflect the collective efforts of various UN agencies in Egypt, including UNICEF, FAO, UNHCR, WFP, ILO, IOM, UNFPA, OCHA, UN-Habitat, UNV, UN Women, and UNRWA.Moreover, UN Egypt booth curators and communication officials engaged in insightful, SDG-focused discussions with the visitors, along with other interactive awareness raising activities designed for visiting children. Additionally, young people had the opportunity to learn about UN volunteering opportunities and the application process.

1 of 3

Story

06 November 2024

WUF12: Egypt’s National Initiative for Smart Green Projects highlighted as model for localizing climate action and promoting sustainable urbanization

As part of the Twelfth Session of the World Urban Forum (WUF12) in Cairo, a high-level session highlighted Egypt’s National Initiative for Smart Green Projects (Egypt SGP) as a leading model for localizing climate action and promoting sustainable urban development through local solutions and innovations.The session was moderated by Ambassador Hisham Badr, the National Coordinator of the initiative, and attended by Dr. Rania Al-Mashat, Minister of Planning, Economic Development, and International Cooperation; Michal Mlynár, Deputy Executive Director of UN-Habitat; Elena Panova, UN Resident Coordinator in Egypt; and Alessandro Fracassetti, UNDP Resident Representative in Egypt. Speakers at the session emphasized the need to scale up successful projects like the National Initiative for Smart Green Projects to achieve a broader global impact, with Minister Mashat emphasizing the significance of multi-sector collaboration to ensure that sustainable solutions are scalable and aligned with global climate goals.Mr. Mlynár commended Egypt SGP as reflecting Egypt’s commitment to localizing climate action and promoting sustainable urban development, noting that the initiative provides local solutions “and we need local solutions.” Ms. Panova congratulated the Government of Egypt for the Egypt SGP, adding that highlighting the initiative at WUF means it can be a model for other countries. She also noted that the UN wide-ranging support to the initiative throughout its three phases. Addressing attending representatives of the winning projects in the initiative, Panova said, “your commitment, your expertise, and your vision shows us how much knowledge, innovation, and passion exists here in Egypt that can be tapped to help address the challenges of climate change.”For his part, Alessandro Fracassetti, UNDP Resident Representative in Egypt, underscored the broader importance of SGP Egypt, stating, "By partnering with SGP Egypt, we are not only driving local climate action but also setting a model for the rest of the world."“By highlighting the achievements of SGP Egypt’s winners, we aim to inspire other countries and regions to adopt a similar model—one that empowers local communities, fosters innovation, and ensures broad participation in the global effort to combat climate change,” said Amb. Hisham Badr, National Coordinator of SGP Egypt. The 12th edition of the World Urban Forum (WUF12), co-hosted by UN-Habitat and the Government of Egypt in Cairo, is focusing on transformative solutions for sustainable urban development. This year’s forum is especially significant as it returns to Africa, with Cairo, a city grappling with both rapid urbanization and climate challenges, providing the backdrop. A key feature of the forum is Egypt’s National Initiative for Smart Green Projects (SGP Egypt), which incorporates green solutions such as sustainable urban design, low-carbon transportation, and energy-efficient buildings into urban planning. The initiative also prioritizes empowering women and youth, acknowledging their vital role in advancing climate action. SGP Egypt is showcased as a global model for climate action, illustrating the effectiveness of local partnerships in addressing urban sustainability issues. The initiative has already supported innovative projects across all 27 of Egypt’s governorates, tackling challenges such as renewable energy, waste management, and low-carbon transportation. These solutions, while tailored to local contexts, are scalable and can serve as inspiration for cities worldwide. The initiative’s success in engaging youth is particularly noteworthy, with many youth-led projects focusing on climate solutions and it offers a global model for addressing climate change through collaborative, local, and innovative solutions.

1 of 3

Video

05 March 2024

"Voices of Impact" podcast opening episode features UN Egypt Resident Coordinator

The United Nations Information Centre in Cairo announced the launch of its new podcast, "Voices of Impact: UN in Egypt", with the UN in Egypt Resident Coordinator, Elena Panoa, being its first guest. This flagship podcast is set to shed light on the significant work carried out by the United Nations in Egypt, marking an important milestone in the enduring and successful partnership between the United Nations and Egypt, as a founding member of the international organization.“Voices of Impact: UN in Egypt" serves as an inspiring platform to explore and highlight the impactful initiatives, programs, and collaborations led by the United Nations within the Egyptian context. Through engaging discussions, interviews, and narratives, the podcast aims to showcase the multifaceted efforts undertaken to address pressing global challenges while fostering development, sustainability, and peace in Egypt and beyond.A wide array of perspectives will be presented, including UN officials, governmental and non-governmental organization representatives, experts, influencers, beneficiaries, and community leaders. The podcast will provide a comprehensive and insightful overview of the United Nations' invaluable contributions to Egypt's development journey and its commitment to leaving no one behind.As the world faces increasingly complex challenges, the podcast will underscore the significance of multilateralism and international cooperation in tackling global issues effectively, by highlighting success stories, innovations, and collaborative partnerships. "Voices of Impact: UN in Egypt" aims to inspire individuals, communities, and stakeholders to actively contribute to positive change and sustainable development efforts.

1 of 3

Story

02 July 2025

UN's Panova says Egypt deeply committed to placing food systems, food security, and nutrition at heart of national development priorities

Elena Panova, the United Nations Resident Coordinator in Egypt, stated that the launch of the National Operational Plan for Food and Nutrition Systems 2025–2030 and the Roadmap to Accelerate Anemia Reduction in Egypt reflects the country's deep and sustained commitment to putting food systems, food security, and nutrition at the core of its human capital development agenda—and making them an essential component of its national development priorities.In a speech delivered on behalf of the United Nations Country Team in Egypt, Panova described the National Operational Plan as a transformational, evidence-based, multisectoral effort. She emphasized that transforming food systems and improving nutrition outcomes is a shared national endeavor requiring broad collaboration across sectors to maximize impact. Panova noted that the launch follows a series of major national strategies and investments, including Egypt’s National Food and Nutrition Strategy (2022–2030), the recently launched National Stunting and Malnutrition Prevention Program, the Takaful and Karama Program, the “First 1,000 Days” initiative, and the Egyptian Code of Marketing Breastmilk Substitutes and Baby-Friendly Health Facility accreditation. She called these programs “clear expressions of Egypt’s progress and ambition.”She described the Anemia Reduction Roadmap as a wise investment for Egypt, noting that every $1 invested in reducing anemia could generate up to $12 in economic returns. The roadmap, she added, will improve the health of pregnant women and their children and could also enhance academic performance among students.“We view both the National Operational Plan for Food and Nutrition Systems and the Roadmap to Accelerate Anemia Reduction not only as means to improve food and nutrition security but as levers for broader social and economic outcomes,” Panova said. "Economic prosperity, social cohesion, and national resilience begin with a food ecosystem that is not only nutrition-sensitive but also addresses inequities and reduces gaps by reaching the most vulnerable population groups, including women, children, the elderly, and others,” she added.Panova presented four critical enablers to ensure the successful implementation of the plan:Strong multisectoral coordination mechanisms to ensure alignment and convergence across all sectors and systems—health, agriculture, education, and social protection.Robust accountability and monitoring frameworks to track progress, promote transparency, and drive continuous improvement.Investment in data systems and evidence generation, enabling timely and informed policy decisions and effective scaling of successful approaches.Sustainable financing and capacity development, ensuring national ownership and long-term resilience of systems.In conclusion, Panova affirmed the United Nations’ strong commitment to supporting these enablers—whether through technical assistance, policy guidance, institutional capacity building, or innovation and knowledge exchange.

1 of 5

Story

01 July 2025

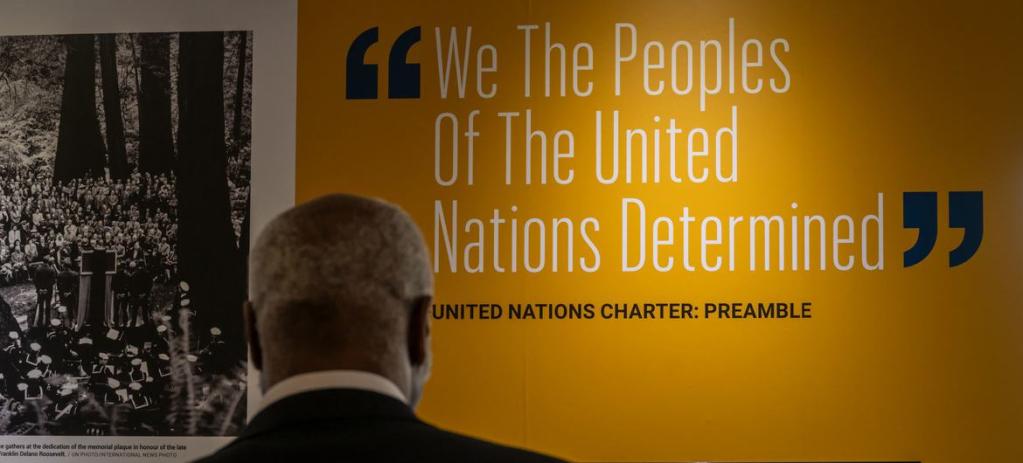

Eighty years on, UN Charter marked by reflection, resolve – and a run

It wasn’t an average Thursday morning in Manhattan. In the early hours, UN diplomats (and UN News) hit the streets in their sneakers – from Times Square to East River – following a route that traced the shape of “UN@80”. Inside the General Assembly Hall, delegates gathered to commemorate the 80th anniversary of its signing.They reflected on the past eight decades in which the UN helped rebuild countries after the Second World War, supported former colonies’ independence, fostered peace, delivered aid, advanced human rights and development, and tackling emerging threats like climate change.To save succeeding generations from the scourge of warGeneral Assembly President Philémon Yang described the moment as “symbolic” but somber, noting ongoing conflicts in Gaza, Ukraine and Sudan, and the growing challenges to multilateralism.He urged nations to choose diplomacy over force and uphold the Charter’s vision of peace and human dignity: “We must seize the moment and choose dialogue and diplomacy instead of destructive wars.”Secretary-General António Guterres echoed this call, warning that the Charter’s principles are increasingly under threat and must be defended as the bedrock of international relations.“The Charter of the United Nations is not optional. It is not an à la carte menu. It is the bedrock of international relations,” he said, stressing the need to recommit to its promises “for peace, for justice, for progress, for we the peoples.”Carolyn Rodrigues-Birkett, Security Council President for June, emphasized the urgency of renewed collective action to address emerging global threats.“Let this 80th anniversary of the Charter be not just an occasion for reflection, but also a call to action,” she urged.UN Photo/Loey FelipeGeneral Assembly commemorates 80th anniversary of the signing of UN Charter.To unite our strength to maintain international peace and securityEighty years ago, on 26 June 1945, delegates from 50 countries gathered in San Francisco to sign a document that would change the course of history.Forged in the aftermath of the Second World War, by a generation scarred by the Great Depression and the Holocaust and having learnt the painful lessons of the League of Nations’ collapse, the Charter of the United Nations represented a new global pact.Its preamble – “We the peoples of the United Nations” – echoed the determination to prevent future conflict, reaffirm faith in human rights, and promote peace and social progress.That very document, preserved by the United States National Archives and Records Administration, has returned – for the first time in decades – to the heart of the institution it founded.Now on public display at UN Headquarters through September, the original Charter stands as a powerful symbol: not just of a past promise, but of an enduring commitment to multilateralism, peace and shared purpose. Video: UN Charter returns to UN HeadquartersTo promote social progress and better standards of lifeMore voices – from the presidents of the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ) – also took the floor, reaffirming the enduring relevance of the Charter and the need to defend it.Bob Rae, ECOSOC President, drew an arc through human history to underscore the UN’s relative youth – just eight decades old in a global context of millennia.“We currently have the advantage of being able to lucidly look at what we have accomplished, while also recognizing our successes and failures,” he said, holding up a copy of the Charter once used by his father.“The United Nations is not a government and the Charter is not perfect,” he said, “but it was founded with great aspirations and hope.”ICJ President Judge Yuji Iwasawa reflected on the progress since 1945 and the challenges still facing the global community.“In the 80 years since the drafters of the Charter set down their pens, the international community has achieved remarkable progress. However, it also faces many challenges,” he said. “The vision of the Charter’s drafters to uphold the rule of law for the maintenance of international peace and security, remains not only relevant but indispensable today.”UN Photo/Loey FelipeJordan Sanchez, a young poet, speaks at the General Assembly during the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the signing of the UN Charter.To reaffirm faith in fundamental human rightsIn a powerful reminder that the Charter speaks not only to the past but to future generations, Jordan Sanchez, a young poet took the stage.Her spoken word piece, Let the Light Fall, evoked not declarations, but feelings of hope and vision for a better world.“Let the light fall,” she began, “on fallen faces hidden in the shadow of scorn…where may the children run towards the light of your face, towards the warmth of your presence and the stillness of your peace.”“There is no fear, only abundance, of safety, of security, of knowing there will always be enough light for me” she said, describing a dreamscape of Eden restored – not a paradise lost, but glimpsed in justice, fairness and shared humanity.“Let us be bold enough to look down and take it, humble enough to kneel down and bathe in it, loving enough to collect and share it, and childish enough to truly, truly believe in it.”The equal rights of men and womenAs the world marks 80 years of the UN Charter, it’s worth remembering that its promise of equal rights for men and women was hard-won from the very start.In 1945, just four women were among the 850 delegates who gathered in San Francisco to sign the document, and only 30 of the represented countries granted women the right to vote.In a 2018 UN News podcast, researchers spotlighted these overlooked trailblazers – and asked why the women who helped shape the UN’s founding vision are so often left out of its story.

1 of 5

Story

29 May 2025

Standing Between Conflict and Hope: Time to Equip UN Peacekeepers for Tomorrow's Challenges

Joint Op-ed by Ambassador Khaled El Bakly, Assistant Minister for Foreign Affairs for Multilateral & International Security Affairs Elena Panova, UN Egypt Resident Coordinator As the United Nations marks its 80th anniversary, the legacy of UN peacekeeping stands as one of the clearest and most enduring expressions of multilateral cooperation. For nearly eight decades, the service and sacrifice of Blue Helmets have saved and changed lives—helping countries navigate the difficult path from war to peace.From Cyprus to Lebanon, and from the Central African Republic to South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, more than 76,000 civilian, military, and police personnel currently serve in 11 missions around the world. These men and women offer a lifeline to millions living in some of the world’s most fragile political and security environments.In light of these growing pressures, it is essential to rethink the role of peacekeeping within the broader international peace and security architecture. As President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi has rightly asserted “peacekeeping—while a vital tool of the international community—should not be viewed as the sole means of maintaining peace”. H.E further emphasized that “it cannot substitute preventive diplomacy, mediation, peacebuilding, or the political, economic, and social measures necessary to address root causes and mend societal fractures”, underscoring that “peacekeeping must not become the default or immediate response to every crisis”.This year’s International Day of UN Peacekeepers is observed under the theme “The Future of Peacekeeping”—a theme that could not be more timely or relevant. Peacekeeping today faces mounting and unprecedented challenges. Conflicts are growing longer, deadlier, and more complex. They increasingly spill across borders and are exacerbated by terrorism, organized crime, cyber warfare, disinformation, and the weaponization of technology. Climate change, meanwhile, deepens instability in already-vulnerable regions. And divergent views within the UN Security Council have made consensus more elusive — slowing the pace of action, precisely when urgency is most needed.As UN Secretary-General António Guterres bluntly put it: “Trust is in short supply among—and within—countries and regions… This is a grim diagnosis, but we must face facts.” Among the most urgent issues is the growing and persistent mismatch between what peacekeeping missions are asked to achieve and the resources that are not available to do so. This undermines effectiveness and places peacekeepers in situations “where there is little or no peace to keep”.The Pact for the Future, adopted at the 2024 Summit of the Future, offers a moment of reckoning—and opportunity. It affirms that peace operations can only succeed when backed by political will and accompanied by inclusive strategies that address the root causes of conflict. It rightly emphasizes the need for peacekeeping missions to be supported by predictable, adequate, and sustained financing.The Pact also mandates a comprehensive review of UN peace operations—a chance to rethink and reform the peacekeeping model. Today’s high-risk environments demand that missions be equipped with the right tools, partnerships, and strategies to protect civilians and support peacebuilding effectively.Egypt, through its 65 years of active participation in United Nations peacekeeping has long demonstrated a strong, sustained and unwavering commitment to the purposes and principles of the United Nations Charter. Since it first deployed troops to the UN Operation in the Congo in 1960, Egypt has contributed over 30,000 of its sons and daughters to 37 missions across 24 countries and has consistently remained one of the top contributors of uniformed personnel to UN peacekeeping. Egypt currently has 1205 peacekeepers, including women, serving across five missions in AfricaEgypt’s longstanding record of service and sacrifice in peacekeeping is globally recognized. This is reflected in its re-election as Rapporteur of the UN Special Committee on Peacekeeping Operations, its recent election to the UN Peacebuilding Commission, and its appointment as co-facilitator for the upcoming 2025 Peacebuilding Architecture Review in both the General Assembly and the Security Council.Egypt’s leadership in peacekeeping is not limited to troop contributions. It plays an active role in shaping strategic thinking around reform. Through the Cairo International Center for Conflict Resolution, Peacekeeping and Peacebuilding (CCCPA)—an African Union Center of Excellence. Egypt has championed context-sensitive, innovative, and inclusive peace operations. The CCCPA emphasizes prevention, civilian protection, and regional partnerships while strengthening the participation of women in peacekeeping, in line with the Women, Peace and Security agenda. Through the CCCPA annual Aswan Forum, Egypt further promotes African-led solutions and stronger peacekeeping–peacebuilding synergies. This work, carried out in close cooperation with the UN in Egypt, is a prime example of effective South-South cooperation and the value of locally driven solutions. Egypt also actively contributes to training African and international uniformed peacekeepers through specialized facilities operated by the Ministry of Interior via the Egyptian Center for Peacekeeping Operations, and by the Ministry of Defense through its Liaison Agency with International Organizations (LAWIO).Egypt is also a staunch supporter of the UN Secretary-General’s Action for Peacekeeping (A4P) initiative. In 2018, Egypt convened a landmark high-level international conference aimed at improving peacekeeping effectiveness. The event led to the “Cairo Roadmap for Peacekeeping Operations,” a concrete framework of shared commitments that was later endorsed by the African Union in 2020. This year, as we remember the 4,430 peacekeepers who have given their lives in the pursuit of peace, we must go beyond commemoration by upholding the principles for which they paid the ultimate sacrifice. Over 60 Egyptian peacekeepers have sacrificed their lives while serving as part of UN operations across the globe. Their sacrifice is a sobering reminder of the growing risks peacekeepers face, and our collective duty to ensure they are provided with the necessary means to fulfill their mandates.At the recently concluded 2025 UN Peacekeeping Ministerial in Berlin this May, Egypt reaffirmed its strong commitment to advancing UN peacekeeping through planned deployments, the preparation of well-trained officers, and expanded training efforts. It pledged to provide specialized capabilities, deploy qualified personnel to UN missions, and enhance training in coordination with international partners. Egypt also highlighted the importance of integrating technology, drawing on lessons from regional transitions, and promoting gender parity—underscoring its intention to surpass the UN’s targets for women's participation in uniformed roles.As the United Nations continues to face significant challenges and in the context of a region affected by multiple conflicts, Egypt has stood firm as a staunch and reliable partner to global peace and security. Furthermore, Egypt has expressed its readiness to provide all necessary support for the UN80 initiative this year in order to help make it a success to achieve effectiveness and rationalization to help meet the acute financial challenges faced by the United Nations and peacekeeping. In that regard, Egypt’s readiness and preparedness to host United Nations’ agencies, programs and offices that might be up for relocation as per the UN80 initiative is to be highly commended. Egypt’s strategic location—at the crossroads of Africa, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East—positions it as a natural hub for connectivity and cooperation. Its central time zone and proximity to key regions make it an ideal and cost-effective location, reducing travel time and facilitating seamless coordination. With direct access to both the Red Sea and the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal - a vital artery of global trade - Egypt offers unmatched maritime connectivity. It’s highly connected international airports and geographical proximity to conflict zones further enhances its relevance as a center for diplomacy, crisis response and peacekeeping efforts.Egypt’s vast experience with peacekeeping and related provision of humanitarian assistance are certainly also worth highlighting as advantageous. As host to multiple international and regional organizations and offices including the seat of the League of Arab States and with over 140 represented embassies in Cairo, Egypt remains a geo-political hub with an already strong United Nations’ presence, a modern infrastructure, and well-recognized levels of safety. As the Secretary-General has said: “Now more than ever, the world needs the United Nations—and the United Nations needs peacekeeping that is fully equipped for today’s realities and tomorrow’s challenges.” Peacekeeping missions are under strain. However, with renewed multilateral resolve, adequate resourcing, and bold reforms, we can empower UN peacekeepers to remain a vital force for peace, stability, and hope in a troubled world, and Egypt, in cooperation with the United Nations remains at the forefront of nations providing such support.

1 of 5

Story

23 May 2025

Reimagining Development in a Complex World: UN Egypt retreat mulls new strategies and partnerships to advance national priorities and the SDGs

Cairo - Against the backdrop of rapidly changing global and regional landscape—marked by socio-economic uncertainty and a redefined approach to financing for development—representatives from across the United Nations system in Egypt convened for their annual UN Country Team (UNCT) retreat. The gathering served as a critical moment for reflection and renewed commitment to advancing national priorities and accelerating progress on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Over the course of two days, participants engaged in a series of strategic discussions focused on the changing global and regional socio-economic, political, and security landscape and its implications for UN operations in Egypt. The sessions offered an opportunity to reassess current approaches and explore new strategies for delivering on the UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Framework (UNSDCF)—the central instrument guiding the UN’s development work in Egypt – and supporting Egypt to progress further on the human rights agenda. Taking place only weeks ahead of the 4th International Conference on Financing for Development (FFD4), in Sevilla, Spain, the sessions included a high-level intervention, by Mahmoud Mohieldin, UN Special Envoy on Financing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, who spoke about the global shifts and emerging trends in the development financing landscape and their impact on Egypt’s sustainable development trajectory. While acknowledging existing challenges for Egypt that require a new comprehensive approach for development, Mohieldin also highlighted key advantages for the country when it comes to localization, digitalization and data, along with the potential to benefit from the demographic dividend, encouraging all stakeholders to invest more in human capital as well as in digital infrastructure, in partnership with the private sector. The discussions also underscored the UN’s role in supporting the implementation of Egypt’s Integrated National Financing Framework (INFF), a key tool for mobilizing and aligning resources with national priorities. Deepening engagement with top UNSDCF partners was also on top of the meeting’s agenda, with a high-level discussion including the Ambassadors of Germany, The Netherlands, Norway and Canada, along with EU Head of Development Cooperation and USAID Country Director for Egypt – weighing on the repercussions of the announced Official Development Assistance (ODA) cuts and shifting partner’s priorities globally and in Egypt. The session further reflected on the evolving development cooperation landscape and discussed ways to enhance collective impact. Furthermore, the retreat featured a high-level exchange with H.E. Ambassador Osama Abdelkhalek, Egypt’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, who shared valuable insights into Egypt’s global engagement priorities and opportunities for strengthened collaboration with the UN system, including on the UN80 initiative.The UN Country Team also took time to reflect internally on how to adapt its coordination and partnership strategies in response to these shifting dynamics. This included a review of UN positioning on key country transitions that highlighted the need to put youth at the center of UN programming and advocated for expanded dialogue with the private sector. Throughout the retreat, the Resident Coordinator’s Office (RCO) played a central role in facilitating strategic dialogue and coordination, highlighting the RC system’s ability to convene diverse actors and improve the effectiveness of the UN’s country-level work.“The challenges are immense, but only with our collective ability to lead and come together around key national priorities can we deliver for the people we serve. We will continue to mobilize the UN system and leverage our convening power and work hand in hand with our development partners to support the government of Egypt in its journey to deliver for its people. Our commitment remains clear: to ensure that no one is left behind,” said the UN Resident Coordinator in Egypt, Elena Panova.

1 of 5

Story

25 March 2025

Funding cuts threaten the lives of Sudanese refugees in Egypt

The global humanitarian funding crisis has forced UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, to suspend key life-saving support to refugees in Egypt, leaving tens of thousands of people – including many who fled the war in Sudan – without access to vital medical treatment, child protection services and other forms of aid.The lack of available funds and deep uncertainty over the level of donor contributions this year has forced UNHCR to suspend all medical treatment for refugees in Egypt except emergency life-saving procedures, affecting around 20,000 patients. The suspensions include cancer surgery, chemotherapy, heart surgery and medication for chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension.Among the worst affected will be refugees from Sudan who fled to Egypt following the outbreak of a brutal conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces in April 2023. Egypt has welcomed over 1.5 million Sudanese escaping what is now the world’s worst humanitarian crisis – more than any other country – including some 670,000 registered with UNHCR. Overall, more than 12.5 million Sudanese have been forced from their homes, including over 3.7 million refugees who fled to other countries.‘Many will die’One of those now fearing for their future because of the cuts is 54-year-old Abdelazim Mohamed, who fled Sudan’s capital, Khartoum, with his wife during the first months of the war, in part because treatment for his serious and long-standing heart condition became impossible to find.“When life became unbearable back home, especially because there were no health facilities operating and finding medicine was very difficult, I felt that staying in Sudan with my condition would be suicide,” he said.UNHCR Public Health Officer Jakob Arhem, based in Cairo, explained that in addition to escaping conflict and violence, access to health care was a key factor for many Sudanese refugees who have arrived in Egypt. “The Sudanese health system was one of the first things that collapsed after the onset of fighting, and many of the families who fled did so with sick members who could no longer find treatment in Sudan,” he said. However, while refugees have been granted access to Egypt’s national health system, very few can afford the fees that come with it, Arhem added.“UNHCR set up programmes that make certain health services available to refugees that they otherwise would not afford,” he explained. “The consequences for people who will no longer get our support are hard to measure, [but] many of them will not be able to find the means to pay for health care themselves and they will get sicker, weaker and many will die.“To shut down activities that you know are life-saving is very hard, and the very opposite of what anyone wants to do who has chosen to work as a humanitarian.”‘I don’t know if I’ll make it’After leaving their comfortable home and lives behind, Abdelazim and his wife now live in a small, rented apartment in the sprawling Faisal neighbourhood of Cairo, midway between downtown and the ancient pyramids of Giza.After registering with UNHCR in Cairo shortly after their arrival, Abdelazim was referred to the agency’s health partner and diagnosed with cardiomyopathy and ischemic heart disease. He had two successful procedures to place stents in his coronary arteries. “I was slowly dying, and I knew it, but after the interventions, I could finally see myself living healthily for as long as I am meant to.”But with UNHCR currently unable to provide the medication that keeps his underlying condition in check, he worries that his time is running out. “I fought so hard to survive, but now, I don’t know if I’ll make it. If I can’t afford my medicine, what happens to me? What happens to my wife if something happens to me?”Last year, UNHCR received less than 50 per cent of the $135 million it needed to help more than 939,000 registered refugees and asylum-seekers from Sudan and 60 other countries now living in Egypt. But the drastic reduction in humanitarian funding since the start of this year has led to critical shortages, forcing UNHCR to make impossible choices over which life-saving programmes to suspend or maintain. At present, UNHCR is prioritizing critical life-saving activities and helping the most vulnerable groups, including unaccompanied children and survivors of sexual violence and torture. Yet without an urgent increase in funding, even these programmes are under threat.UNHCR Child Protection Officer in Egypt, Farah Nassef, described one case involving a young Sudanese man who had arrived as an unaccompanied minor. He was receiving full-time care for his mental and physical disabilities, but the support was recently withdrawn due to the current funding situation.“Despite him having no family, no community support, it means that he will be left in an extremely dire and difficult situation,” Nassef said. “We see such cases day in and day out … You see people on some of the worst days of their lives, and often you cannot help them with everything they ask for, or the support you can provide is simply not enough.”UNHCR is calling on all donors – including governments, private companies and individuals – to urgently support refugees and displaced people around the world who are already suffering the devastating impact of reduced funding and support.“The needs of refugees fleeing Sudan are growing by the day, but funding is not keeping pace,” said Marti Romero, Deputy Representative at UNHCR Egypt. “Egypt is under immense strain, and essential services are being pushed to the limit. Without immediate international action, both refugees and host communities will face even greater hardship. We need urgent and sustained support to prevent this crisis from worsening.” Millions of refugees and displaced people worldwide risk losing access to life-saving aid due to brutal cuts in global humanitarian funding. UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, has the expertise, experience and determination to keep protecting people forced to flee, but we urgently need donors – individuals, businesses and governments – to step up. Please donate today to help us reach the most vulnerable. Lives depend on it.

1 of 5

Press Release

30 June 2025

THE SECRETARY-GENERAL -- REMARKS AT THE OPENING OF THE 4TH FINANCING FOR DEVELOPMENT CONFERENCE

Your Majesties, Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, I thank the Government and people of Spain for welcoming us to Sevilla for this important conference. For decades, the mission of sustainable development has united countries large and small, developed and developing. Together, we achieved progress. Reducing global poverty and hunger. Saving lives with stronger health care systems. Getting more children into school. Expanding opportunities for women and girls. And strengthening social safety nets. But today, development and its great enabler — international cooperation — are facing massive headwinds. We are living in a world where trust is fraying and multilateralism is strained. A world with a slowing economy, rising trade tensions, and decimated aid budgets. A world shaken by inequalities, climate chaos and raging conflicts. The link between peace and development is clear. Nine of the ten countries with the lowest Human Development Indicators are currently in a state of conflict. Excellencies, Financing is the engine of development. And right now, this engine is sputtering. As we meet, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development — our global promise to transform our world for a better, fairer future — is in danger. Two-thirds of the Sustainable Development Goals targets are lagging. Achieving them requires an investment of more than $4 trillion a year. But this is not just a crisis of numbers. It’s a crisis of people. Of families going hungry. Of children going unvaccinated. Of girls forced to drop out of school. We are here in Sevilla to change course. To repair and rev up the engine of development to accelerate investment at the scale and speed required. And to restore a measure of fairness and justice for all. Excellencies, The Sevilla Commitment document is a global promise to fix how the world supports countries as they climb the development ladder. I see three areas of action. First — we must get resources flowing. Fast. Countries must lead by mobilizing domestic resources and investing in areas of greatest impact: schools, health care, social protection, decent work, and renewable energy. Unlocking these investments requires strengthening tax systems, and tackling illicit financial flows and tax evasion. And helping developing countries dedicate a greater share of their tax revenues to the systems people need. The Sevilla Commitment’s call on developed countries to double their aid dedicated to domestic resource mobilization to support this. Multilateral and national development banks must unite to finance major investments. This includes tripling the lending capacity of Multilateral Development Banks — and rechanneling Special Drawing Rights that can unlock lending capacity and help developing countries boost investment. We also need innovative funding solutions to unlock private capital. Solutions that mitigate currency risks; That combine public and private finance more effectively, and ensure the risks and rewards of development projects are shared by both the public and private sectors; And that ensure financial regulations assess risk appropriately and support investments in frontier markets. Second — we must fix the global debt system which is unsustainable, unfair and unaffordable. With annual debt service at $1.4 trillion, countries need — and deserve — a system that lowers borrowing costs, enables fair and timely debt-restructuring, and prevents debt crises in the first place. The Sevilla Commitment lays the groundwork: With other aspects, by also creating a single debt registry for transparency, and promoting responsible lending and borrowing; By lowering the cost of capital through debt swaps and debt management support; And through debt service pauses in times of emergency. And third — we must increase the participation of developing countries in the institutions of the global financial architecture. The present major shareholders have a role to play recognizing the importance of correcting injustices and adapting to a changing world. A new borrowers forum will give voice to borrowers for fairer debt resolution and can foster transparency, shared learning and coordinated debt action. And we need a fairer global tax system shaped by all, not just a few. Excellencies, ladies and gentlemen, This conference is not about charity. It’s about restoring justice and lives of dignity. This conference is not about money. It’s about investing in the future we want to build, together. Thank you all for being part of this important and ambitious effort. ***

1 of 5

Press Release

23 June 2025

Statement Attributable to the Spokesperson for the Secretary-General – on Qatar

From the outset of the crisis, the Secretary-General has repeatedly condemned any military escalation in this conflict, including today’s attack by Iran on the territory of Qatar. He further reiterates his call on all parties to stop fighting. The Secretary-General urges all Member States to uphold their obligations under the UN Charter and other rules of international law. Stéphane Dujarric, Spokesman for the Secretary-GeneralNew York, 23 June 2025 *****Office of the Spokesperson for the Secretary-GeneralUnited Nations

1 of 5

Press Release

23 June 2025

Secretary-General's remarks to the UN Charter Day Exhibition [as delivered]

And as we open this exhibition that celebrates our earliest days, we are reminded that the Charter was only the beginning.The ideals it enshrined had to be put into action — by people, by process, and sometimes, by something as simple as a wooden box.In the spring of 1946, at Hunter College here in New York City, the first UN ballot box for the Security Council was opened for a routine inspection before the first vote.To everyone’s surprise, there was already a slip of paper inside.It was a message from the box’s maker — a mechanic named Paul Antonio. Apparently, there have been some Antonios around.He wrote:“May I, who have had the privilege of fabricating this ballot box, cast the first vote?May God be with every member of the United Nations organization and through your noble efforts bring lasting peace to us all – all over the world.”That message — humble, hopeful, and heartfelt — captures the spirit of the United Nations at its founding.And it reminds us why we are here today.Eighty years is a blink of an eye in history.And yet, until the United Nations, humanity never had a single place where every government and all peoples could unite to fix the world and build something better.The UN is a living miracle — and the women and men of the United Nations bring this miracle to life every day and everywhere:Forging peace.Tackling poverty, hunger, and disease.Advancing human rights.Delivering lifesaving aid.And striving to make our organization stronger.Today, our world faces age-old challenges — and newer threats like the climate crisis and runaway technology, not to mention the horrible conflicts we are witnessing.But we have the tools and the norms of international law to guide us, starting with the United Nations Charter.And as we reflect on the artifacts of our founding — the documents, the symbols, the memories — I keep thinking about that note in the ballot box.Paul Antonio never sat in a General Assembly seat.He never gave a speech or signed a treaty.But he believed in what this Organization could become.He believed in us.Eighty years later, I hope we can all carry that same spirit — of quiet conviction, of hope, and of belief in peace — into the future we are building together.And I thank you.

1 of 5

Press Release

20 June 2025

THE SECRETARY-GENERAL -- REMARKS TO THE SECURITY COUNCIL New York, 20 June 2025

Madam President, allow me to make a brief introduction before the briefings of my colleagues Excellencies, There are moments when the choices before us are not just consequential -- they are defining. Moments when the direction taken will shape not only the fate of nations, but potentially our collective future. This is such a moment. To the parties to the conflict – the potential parties to the conflict – and to the Security Council as the representative of the international community, I have a simple and clear message: Give peace a chance. The confrontation between Israel and Iran is escalating rapidly with a terrible toll – killing and injuring civilians, devastating homes, neighborhoods and civilian infrastructure, and attacking nuclear facilities. The world is watching with growing alarm. We are not drifting toward crisis – we are racing toward it. We are not witnessing isolated incidents -- we are on course to potential chaos. The expansion of this conflict could ignite a fire that no one can control. We must not let that happen. Excellencies, It may be easy to list a range of problems that have impacted relations between Israel and Iran in the last decades. But the central question of this conflict is the nuclear question. Non-proliferation is a must for the safety and security of us all. The Non-Proliferation Treaty is a cornerstone of international security. Iran must respect it. And Iran has repeatedly stated that it is not seeking nuclear weapons. Let’s recognize there is a trust gap. The only way to bridge that gap is through diplomacy to establish a credible, comprehensive and verifiable solution – including full access to inspectors of the IAEA, as the United Nations technical agency in this field. For all of that to be possible, I appeal for an end to the fighting and the return to serious negotiations. At this defining moment, I urge this Council to act with unity and urgency for dialogue. And I urge the international community to rally behind the sole path that can deliver lasting peace: diplomacy grounded in international law, including the UN Charter. This is even more crucial given the unfolding horrors in Gaza. Excellencies, The only thing that is predictable is that the consequences of continuing this conflict are unpredictable. Let us not look back on this decisive moment with regret. Let us act -- responsibly and together -- to pull the region, and our world, back from the brink. Thank you.

1 of 5

Press Release

20 June 2025

THE SECRETARY-GENERAL -- MESSAGE ON WORLD REFUGEE DAY 20 June 2025

Many face closed doors and a rising tide of xenophobia. From Sudan to Ukraine, from Haiti to Myanmar, a record number of people are on the run for their lives – while support is dwindling. And host communities, often in developing countries, are shouldering the greatest burden. This is unfair and unsustainable. But even as the world falls short, refugees continue to show extraordinary courage, resilience and determination. And when given the chance, they contribute meaningfully – strengthening economies, enriching cultures, and deepening social bonds. On this World Refugee Day, solidarity must go beyond words. Solidarity must mean boosting humanitarian and development support, expanding protection and durable solutions such as resettlement, and upholding the right to seek asylum – a pillar of international law. It must also mean listening to refugees and ensuring they have a voice in shaping their futures. And it must mean investing in long-term integration through education, decent work, and equal rights. Becoming a refugee is never a choice. But how we respond is. So let us choose solidarity. Let us choose courage. Let us choose humanity. ***

1 of 5

Latest Resources

1 / 11

1 / 11